The Economist's Guide to Causal Forests

A guide to understanding and implementing causal forests for heterogeneous treatment effect estimation, bridging the gap between machine learning and econometrics.

Introduction

With each year, more and more information about the world is being generated. In 2021, the total amount of data created was estimated to have reached 79 zettabyte,

It is evident that as the nature of data evolve, the empirical science analyzing these data must evolve as well. The field of statistics has been embracing this change for some time now, a process that was famously promoted by Breiman (2001)

One issue that lies at the heart of econometrics is estimation of causal effects. Formally, given data on some outcome, treatment, and covariates, \(\{(Y_i, W_i, X_i)\}_{i=1,...,N}\), one is interested in estimating the average treatment effect \(\tau = \mathbb{E}[Y_i(1)-Y_i(0)]\), where \(Y_i(w)\) denotes the potential outcome that unit \(i\) would have if it would be assigned treatment \(w\). In practice, treatment effects can differ considerably between units, so that the aim is often recovery of heterogeneous treatment effects given covariates, \(\tau(x)=\mathbb{E}[Y_i(1)-Y_i(0)\vert X_i=x]\). For example, one might want to estimate the individual-specific effect of a costly policy, to apply it only to individuals who derive sufficient benefit from it.

There are two problems that may render estimation via least squares infeasible. First, in high-dimensional data the number of covariates can easily exceed the number of observations. Second, the heterogeneous treatment effect \(\tau(x)\) may exhibit severe non-monotonicity and involve complex interactions between covariates. Then, even if the number of covariates is only moderately high, estimating the shape of \(\tau(x)\) may require more parameters in the least squares regression than can be estimated precisely.

Where classic least squares methods capitulate before this new type of data, machine learning methods are up to the task. One particular method that has proven itself to scale well with large and complex data is called random forest. In brief, a random forest generates a large number of regression trees, which each approximate a given high-dimensional relationship by a step-function. By randomly varying input data when constructing these trees, the random forest generates many different models and finally averages their predictions.

Unfortunately, although random forests are a powerful tool for analyzing high-dimensional data, they cannot be used out-of-the-box for problems in economic research, for two reasons. First, the trees that make up the random forest are prediction methods; they approximate a given function by balancing the fundamental trade-off between bias and variance of the prediction. Instead, economists require causal methods; unbiased estimates are strictly necessary, at the deliberate expense of higher variance. This point will be explained in more detail later. Second, random forests are like many machine learning methods essentially model-free; they impose little prior structure on the final prediction. In contrast, economics models are often informed by economic theory, and it is not straightforward how to incorporate it when constructing trees.

Causal forests are a groundbreaking method that allows inferring heterogeneous treatment effects using random forests. In doing so, they bridge the gap between machine learning and standard econometrics, allowing detailed causal inference from large data.

This article proceeds as follows. The next section summarizes the core concepts behind regression trees and random forests. The third section explains the conceptual steps to adapt random forests for the estimation of causal effects, and introduces the “state of the art” for estimating causal forests. The final section showcases an application, and discusses limitations and alternatives.

A Quick Summary of Random Forests

A classic version of a tree is the classification and regression tree (CART) as proposed by Breiman et al. (1984)

The partition is generated as follows: The initial node is simply the complete covariate space. Then, this node is repeatedly split in two to minimize prediction mean squared error (MSE) greedily; that is, each split looks for the maximum immediate improvement in MSE. A split must occur in one dimension only: Given some node \(R\), a split is characterized by a covariate \(x_k\) and a corresponding value \(c\). Then, the child node \(R_1\) contains the subset of \(R\) with \(x_k\leq c\), and the child node \(R_2\) contains its complement; the subset of \(R\) with \(x_k>c\). In this fashion, nodes are repeatedly split until a certain stopping criterion is reached, for example until all terminal nodes (“leafs”) contain a pre-specified minimum number of observations.

The procedure is prone to overfitting: With each new split, the tree predicts better the training data, which reduces bias but increases variance of the predictions. To balance this inherent trade-off, one needs to select one tree from the sequence of trees obtained from adding splits. A method for doing so is cost complexity pruning, which introduces a penalty parameter \(\alpha\) on the number of nodes \(T\) that combined with the MSE generates a score \(C_\alpha\) for each tree:

\[C_{\alpha} = MSE + \alpha |T| \ .\]By finding \(\alpha\) through cross-validation, one determines the optimal depth of the tree.

The major advantages of CARTs are their interpretability (the partition makes it transparent how predictions are made), and their computational speed even with high-dimensional data. However, the major disadvantage is that although CARTs often have low bias, they tend to have relatively high variance, so that predictions may change drastically with small changes to the input data. For that reason, Breiman (1996)

From Causal Trees to Causal Forests

We now turn back to our initial problem of estimating heterogeneous treatment effects. Suppose we are given a sample of outcome, treatment, and covariates, \(\{(Y_i, W_i, X_i)\}_{i=1,...,N}\), and assume that treatment is randomized conditional on covariates

\[Y_i(1), Y_i(0) \perp W_i\ | X_i \ ,\]which is typically referred to as unconfoundedness, a necessary condition for identification. We are interested in estimating the conditional average treatment effect (CATE) for some point \(x\):

\[\tau(x)=\mathbb{E}[\tau_i(x)|X_i=x] \qquad\text{where}\qquad \tau_i = Y_i(1)-Y_i(0) .\]There are two main reasons why a random forest consisting of the usual CARTs is not suited for this estimation problem. First, CARTs split and prune to maximize prediction MSE \(\sum_{i=1}^N (Y_i-\hat\mu(X_i))^2/N\), so that the most natural adaptation to our problem would entail targeting estimation MSE \(\sum_{i=1}^N (\tau_i - \hat\tau_i(X_i))^2/N\). However, \(\tau_i\) is never actually observed, rendering this option infeasible. The second reason is that naive splitting will bias estimates, which is a more subtle point. To see why, consider a simple example where the covariate space contains only two elements, \(\mathbb{X}=\{L,R\}\), and we wish to estimate the difference in outcomes \(\Delta=\mathbb{E}[Y_L-Y_R]\). If we try to estimate \(\Delta\) via a tree, we have two choices: Either split the initial node, or not, which results in estimates \(\hat\Delta=0\) or \(\hat\Delta=\overline{Y}_L-\overline{Y}_R\), where \(\overline{Y}_\ell\) defines the average outcome in leaf \(\ell\in\{L,R\}\). The most natural splitting rule places a split if and only if \(\overline{Y}_L-\overline{Y}_R>c\) for some \(c\in\mathbb{R}\). However, this procedure introduces selection bias: For example, if due to sampling variability we observe \(\overline{Y}_L-\overline{Y}_R>c\), our estimate is biased upwards: \(\hat\Delta=\mathbb{E}[Y_L-Y_R\vert\overline{Y}_L-\overline{Y}_R>c]>\Delta\).

Causal Trees

Athey and Imbens (2016)

Honest approach. Honest estimation solves the problem of selection. Employing the simplified example above, even if due to sampling variability we happen to observe \(\overline{Y}_L-\overline{Y}_R>c\) and place a split, the final estimate \(\hat\Delta\) will be computed with an independent sample, and thus be unbiased. However, it should be noted that this procedure entails a trade-off: By splitting observations into a training sample for partitioning and an estimation sample for calculating effects, both steps will be conducted using less observations. Therefore, the honest approach makes a sacrifice in variance for improvements in bias.

Moreover, note that honest estimation modifies the rules for splitting and cross-validation. To illustrate this fact, consider the splitting target of a CART, which for a given training sample \(S^{tr}\) and partition \(\Pi\) can be written

In the honest approach, the equivalent would be

\[MSE_\mu(S^{tr}, S^{est}, \Pi) = \sum_{i\in S^{tr}} (Y_i-\hat\mu(X_i;S^{est},\Pi))^2 \ .\]However, since the point is not to use the estimation sample \(S^{est}\) for partitioning, the data in \(S^{est}\) are treated as a random variable during the tree-building phase. Therefore, the target is expected MSE

\[EMSE_\mu(S^{tr}, S^{est}, \Pi) = \mathbb{E}_{S^{est}} [MSE_\mu(S^{tr}, S^{est}, \Pi)] \ .\]Splits are placed to improve an approximation \(\widehat{EMSE}_\mu(\cdot)\), and similarly for cross-validation.

Targeting treatment effect heterogeneity. Recall that splitting and cross-validation also need to be adapted for estimating (unobserved) treatment effects as opposed to (observed) goodness of fit. The key insight here is that for minimizing the MSE of the treatment effect \(MSE_\tau = \sum_i (\tau_i - \hat\tau_i(X_i))^2\), it is sufficient to maximize the variance of of \(\hat\tau(X_i)\) in each child node. For an illustration, consider again the conventional (non-honest) CART target

\[MSE_\mu = \sum_{i\in\mathcal{I}} (Y_i-\hat\mu(X_i))^2 = \sum_{i\in\mathcal{I}} Y_i^2 - \sum_{i\in\mathcal{I}} \hat\mu(X_i)^2 \ .\]Since \(\sum_{i\in\mathcal{I}} Y_i^2\) is unaffected by splitting decisions, \(MSE_\mu\) can be minimized by maximizing \(\sum_{i\in\mathcal{I}} \hat\mu(X_i)^2\), which is equivalent to maximizing \(Var(\hat\mu(X_i))=\sum_{i\in\mathcal{I}} \hat\mu(X_i)^2 - \big(\sum_{i\in\mathcal{I}} \hat\mu(X_i)\big)^2\) since \(\sum_{i\in\mathcal{I}} \hat\mu(X_i) = \sum_{i\in\mathcal{I}} Y_i\) for all trees. In other words, we can minimize the MSE of \(\hat\mu(\cdot)\) by picking splits that maximize the variance of \(\hat\mu(\cdot)\). Analogously, causal trees maximize a variance estimate of \(\hat\tau(X_i)\) at each split. Intuitively, targeting high treatment effect variance will lead to large heterogeneity in treatment effects across nodes, which is exactly the goal.

As before, this splitting rule needs to be adapted to the honest approach, which entails estimating a target \(\widehat{EMSE}_\tau(\cdot)\), and similarly for cross-validation.

Causal Forests

Although causal trees allow inferring consistent estimates for conditional average treatment effects, they are not ideal for practical applications. First, just like common CARTs, causal trees can be sensitive to small changes in inputs, and therefore in general have high variance. Second, they tend to generate relatively large leaves, in which the assumption of unconfoundedness is unlikely to hold: Usually, observations in a large leaf will differ in their probability of receiving treatment, so that naive treatment effect estimates will be biased. Third, no asymptotic theory is available for estimates obtained from causal trees, which might make it difficult to justify their application in economics papers.

Wager and Athey (2018)

As in Breiman (1996)

State-of-the-Art Causal Forests

In practice, the inventors prefer a slightly different implementation of causal forests that is applicable to a wider range of estimation problems and promises better performance.

The main problem with causal forests as in Wager and Athey (2018)

When estimating a causal forest within the generalized random forests framework, the implementation bears three main differences to the outline above: First, the causal forest is now only used to infer observation weights that are then used for estimating a local moment condition. Second, the splitting criterion is approximated by a linear function. Third, the authors recommend regressing out the effect of covariates before estimation, which is referred to as orthogonalization.

Local moment condition. Consider any estimation problem whose solution \(\theta(x)\) solves some moment condition

\[E[\psi_\theta|X_i=x]=0 \ .\]Then, taking inspiration from similar approaches in nonparametric regression, it is straightforward to estimate \(\theta(x)\) using the locally-weighted sample analog

\[\hat\theta(x) = \arg \min_\theta \Big\|\sum \alpha_i(x) \psi_\theta\Big\|_2 \ ,\]where \(\alpha_i(x)\) are weights indicating the “closeness” of observation \(i\) to some test point \(x\). These weights will be estimated via a causal forest.

To clarify the above point: In a classical random forest, each tree computes its own treatment effect estimate for the test point \(x\), and the final estimate is the average of these individual estimates. In a generalized random forest, one does not use the estimates of the trees, but only the partitions they generate. Intuitively, if an observation is in the same leaf as \(x\) in many trees of the forest, it can be interpreted as being very similar, and therefore important for estimating any quantity of interest at \(x\). Moreover, being in the same leaf is more important if the considered leaf is small, since that observation “survived” many splits together with \(x\). Conversely, an observation that is not “close” to \(x\) in many trees is likely less important for estimating \(\theta(x)\).

The idea of inferring local weighting from a random forest is illustrated in the figure below. Formally, when growing a total of \(B\) trees, we can define as \(\alpha_{bi}\) the importance of observation \(i\) in tree \(b\), and as \(\alpha_i(x)\) the overall weight of \(i\) for \(x\):

\[\alpha_{bi}(x) = \frac{\mathbf{1}(\text{$i$ is in same leaf as $x$})}{\text{no. observations in same leaf as $x$}} \qquad\text{and}\qquad \alpha_i = \frac{1}{B} \sum_{b=1}^B \alpha_{bi}(x) \ .\]

Splitting. As before, trees are built by greedy splitting to maximize heterogeneity in treatment effects. Although the estimation problem is framed differently, the final target is still minimizing the MSE of \(\theta(x)\) (the CATE, \(\tau(x)\), in our case). Therefore, the ideal splitting criterion would be exactly the same as in Athey and Imbens (2016)

Athey, Tibshirani, and Wager (2019)

Orthogonalization. The authors stress that performance of a causal forest can be improved by first regressing out the effects of the covariates on outcomes and treatment, which makes it more likely that the unconfoundedness assumption holds. This procedure is similar to the idea of double machine learning as proposed by Chernozhukov et al. (2018a)

Athey, Tibshirani, and Wager (2019)

The table below summarizes the core conceptual steps when estimating heterogeneous treatment effects at some test point \(x\) via a causal forest, as currently implemented in the R-package grf.

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| 1. Orthogonalize | Obtain residuals $\tilde{Y}_i = Y_i - m(x)$ and $\tilde{W}_i = W_i - e(x)$ via classical random forests. |

| 2. Generate causal forest | For $b=1,...,B$:

|

| 3. Compute weights | Infer the importance of each observation in the full sample for point $x$. |

| 4. Solve sample analog of local moment condition | This can be done by a standard automatic solving procedure. |

Applications and Discussion

For an exemplary application of causal forests, consider 401(k) eligibility in the US. Some firms offer a private retirement savings plan to their employees, called a 401(k), where contributions by the employee may be matched by the company. The program was designed by the US Congress with the intent to encourage individual retirement savings. For evaluating the success of the program, it is therefore critical to understand how much eligibility for the 401(k) plan increases household savings.

I follow the analysis by Chernozhukov and Hansen (2004)

Implementation in R

Let’s walk through the implementation of a causal forest using the grf package in R. We’ll start by loading the necessary libraries and data.

Data Preparation

First, we load the required packages and import the data:

# Load required libraries

library(grf)

library(foreign)

# Set seed for reproducibility

set.seed(05012022)

# Import data

data <- read.dta("sipp1991.dta")

# Extract outcome variable (net total financial assets)

y <- unlist(data["net_tfa"])

# Extract treatment indicator (401k eligibility)

d <- unlist(data["e401"])

# Extract control variables

x_df <- data[c("age", "inc", "educ", "fsize", "marr",

"twoearn", "db", "pira", "hown")]

x <- as.matrix(x_df)

The data includes:

- Outcome (

y): Net total financial assets - Treatment (

d): 401(k) eligibility indicator - Covariates (

x): Age, income, education, family size, marital status, two-earner status, defined benefit pension, IRA participation, and home ownership

Training the Causal Forest

Now we can train the causal forest. The grf package handles orthogonalization, sample splitting, and weight computation automatically:

# Estimate causal forest

tau.forest <- causal_forest(x, y, d, num.trees = 12000)

# Compute average treatment effect on the treated (ATET)

average_treatment_effect(tau.forest, target.sample = "all")

A causal forest implemented via grf using default parameters and generating 12000 trees finds an average treatment effect of 7990, suggesting that eligibility induces households to own roughly $8000 more across all assets. This result is perfectly in line with the estimates from Chernozhukov et al. (2018a)

Analyzing Treatment Effect Heterogeneity

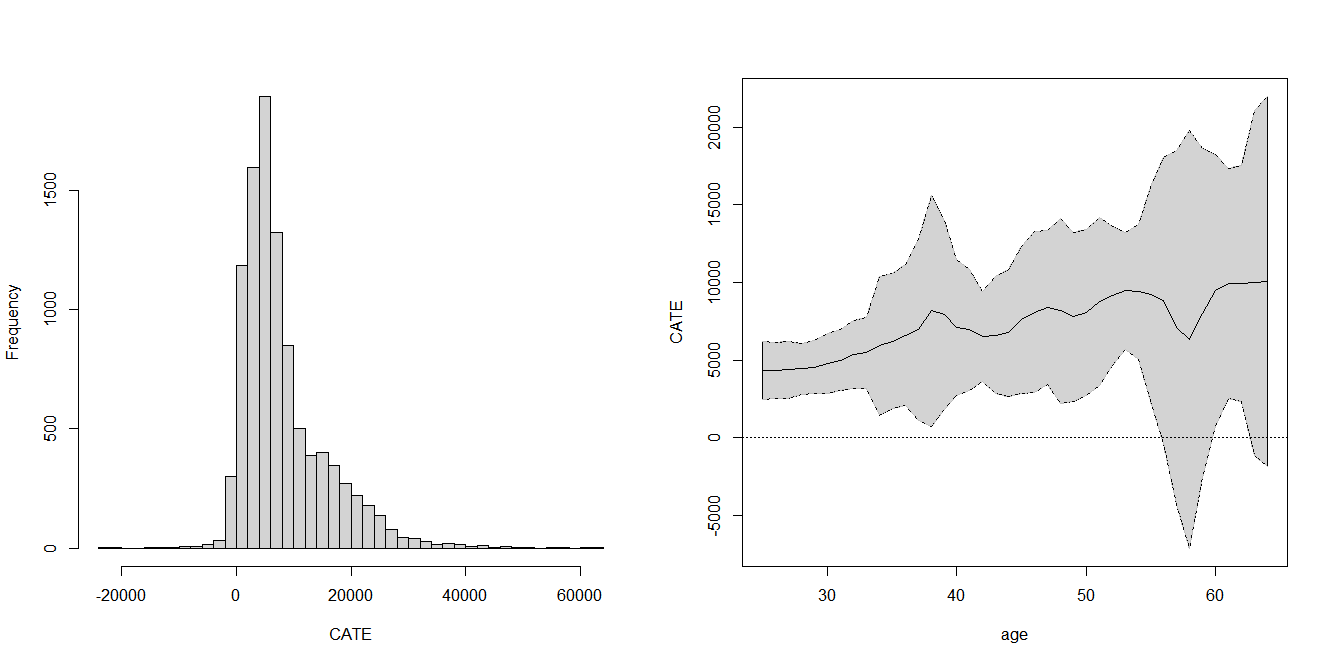

However, with our causal forest we can go beyond and estimate heterogeneity of the treatment effect. Let’s first look at the distribution of individual treatment effects:

# Get out-of-bag predictions

tau.hat.oob <- predict(tau.forest)

# Plot histogram of treatment effects

hist(tau.hat.oob$predictions, breaks=40,

main="", xlab="CATE")

Next, we can examine how treatment effects vary with specific covariates, such as age:

# Create test data varying age while holding other variables constant

a <- sort(unique(x_df$age))

al <- length(a)

x.avg <- colMeans(x)

X.test <- matrix(x.avg, al, 9, byrow = TRUE)

X.test[, 1] <- a

# Predict treatment effects for test data

tau.hat <- predict(tau.forest, X.test, estimate.variance = TRUE)

sigma.hat <- sqrt(tau.hat$variance.estimates)

X <- X.test[, 1]

CIupper <- tau.hat$predictions + 1.96 * sigma.hat

CIlower <- tau.hat$predictions - 1.96 * sigma.hat

# Plot treatment effects by age with confidence intervals

plot(X, tau.hat$predictions,

ylim = range(CIupper, CIlower, 0, 2),

xlab = "age", ylab = "CATE", main="",

type = "l", lwd=2, col="black")

lines(X, CIupper, lty = 2, lwd=1, col="grey")

lines(X, CIlower, lty = 2, lwd=1, col="grey")

polygon(c(X, rev(X)), c(CIupper, rev(CIlower)), col = "lightgrey")

lines(X, tau.hat$predictions, type = "l", lwd=1, col="black")

lines(X, CIupper, lty = 2, lwd=1, col="grey")

lines(X, CIlower, lty = 2, lwd=1, col="grey")

abline(h=0, lty=3)

Results

The left panel of the figure below reports the distribution of CATE estimates across all observations, which are as expected mostly positive, but exhibit large variation. The right panel shows how the CATE estimates and their 95% confidence intervals differ with age for a hypothetical average individual. Unsurprisingly, the estimated effect of 401(k) eligibility is larger for older individuals, even after conditioning on income. This result underlines the importance of convincing also young individuals that saving for retirement is sensible.

Right: Estimated conditional average treatment effect given age, with 95% confidence intervals.

Discussion

Through the eyes of an economist, the following might be good reasons for using causal forests in academic research. First and foremost, they are a powerful tool for uncovering heterogeneity in treatment effects, even with many covariates and under complex functional forms. Second, the generalized random forests framework allows tackling a wide range of empirical problems, including both binary and continuous treatment, and instruments. Moreover, the same framework can be used for other standard estimation problems in economics as well. Third, the estimation procedure is similar to the method of moments estimator commonly used in economics, and therefore arguably intuitive. Moreover, the weighting makes transparent which observations play a key role for the final estimates. Fourth, causal forests are easy to implement through the openly available and well-documented R-package grf. Finally, the approach has similar asymptotic properties as the workhorse models in economics, and is therefore well-justified.

Despite their benefits, causal forests are not a one-size-fits-all solution. First, the estimates generally depend on many tuning parameters which may require careful calibration. For an economist, calibrating the model might be an unusual experience since the optimal parameter values cannot be inferred from economic theory, but rather from trial and error as well as experience. Automatic calibration via cross-validation is possible, but may require a large number of observations while at the same time it is usually difficult to judge what exactly “large enough” is. Second, the package grf is so far only available in R, which might require some researchers to spend time getting acquainted with the language. Finally, one should consider that not many researchers in economics are familiar with causal forests, and some might hold reservations against a method they do not understand. Thus, compared to standard methods in economics, one might need to put extra effort into convincing their audience that their findings are correct.

As a last note, this article would be incomplete without mentioning double machine learning as introduced by Chernozhukov et al. (2018a)